Overdiagnosis: how early detection changes the definition of disease itself [3]

Can you have had cancer if you were never sick?

Welcome to Limits of Inference! The post below is not intended as a self-standing piece. This is some supplementary context in support of a previous article. To get an introduction to the problem of overdiagnosis, check out the original piece here.

Questions? Concerns? Let me know in the comments. Also, subscribe below.

How to identify overdiagnosis of a disease

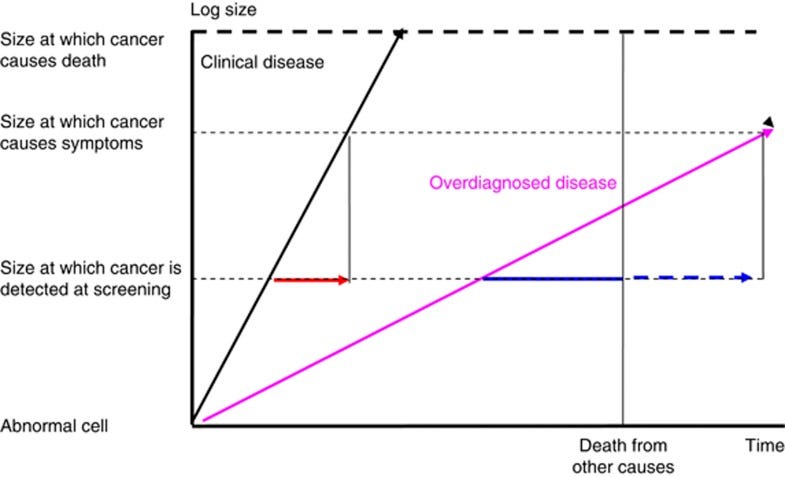

The graph below demonstrates a common framework, invented in the context of cancers, to identify overdiagnosis. According to this framework, overdiagnosis is the likely explanation anytime an increase of cases (incidence) does not coincide with an increase in death (mortality). Diseases are defined by the impact on health, not the biochemical evidence that corresponds to disease. If we find a real disease, the most important health consequence of the disease (i.e., death) should increase as the incidence does.

Since the number of COVID-19 cases has gone up by an order of magnitude from the spring peak to the winter, and the deaths per day are only now approximately the same as the peak from the original NYC-NJ outbreak, it is straightforward to infer that we are substantially overdiagnosing COVID-19.

However, it is worth being careful here since there are other explanations consistent with the data. The early COVID-19 data were collected under a very different context. In March, doctors often used ventilators, a dangerous treatment with substantial side effects of its own, to treat COVID-19. This ineffective and sometimes deadly treatment may have contributed to some of the early excess deaths. We also didn't have any tests back in March and April, so our estimate of the spread of the disease is lower than what we would observe with our testing infrastructure today. Plus, the disease was entirely new, so its geographic reach has almost certainly increased. Given this context, a plausible alternate explanation exists other than overdiagnosis: it could be that COVID-19 was always not particularly deadly. This is probably part of the truth. This would mean the overdiagnosis problem is less severe, but also, the pandemic would be a less severe health crisis overall.

Why early detection leads to more overdiagnosis

There is an important parallel between COVID-19 and cancer— early detection is considered of paramount importance for clinical outcomes. Early detection is valuable because modern treatments work better on early-stage cancers. Similarly, early detection of COVID-19 may prevent further spread.

In cancer, the problem with trying to diagnose earlier and earlier is that it leads to a sliding threshold problem — the line between diseased and healthy gets moved so that more and more people are defined as sick. This changed definition of disease is another common source of overdiagnosis and a much more contentious one. For example, some scientists started treating lesions with chemotherapy when it was previously considered precancerous and just something to watch. Scientists started considering asymptomatic infections as cases of the disease, COVID-19, instead of just infections.

It is only practical to change the definition of a disease once we can observe it, so a new test or technology is often a prerequisite for a definition change (to find infections without symptoms or smaller precancerous lesions). If we look back at history, we see evidence of a more troubling dynamic. New technology tends to cause a change in disease definition. A small group of scientists invent a new test looking for an early indicator of existing disease (usually one they also identified as important). In early experimental settings, the new tests find more cases of disease even earlier than before. That is counted as a win since the community values early detection. This leads to an official institution-backed change in the disease's definition to include all occurrences of the early indicator as clinical evidence of disease. More people are diagnosed and treated for the disease. The disease gets more funding because it now is measured to be a bigger health risk. Then, a new scientist claims to have invested in a new, better test. The cycle begins again.

This cycle can easily become a game of how many things can we designate disease, disconcertingly independent of the resulting health outcomes. This was the observation that motivated the invention of the overdiagnosis framework above.

Diseases are human constructs. We observe something, call it a disease, and then treat the disease. Nothing is stopping us from labeling all of human existence a disease. To be clear, this is a controversial claim. Not everyone agrees this is happening in any one circumstance. Instead of staking a strong claim today, I will say this, keep an eye out for situations where, for whatever reason, the definition of the disease itself seems to change to make the point.

The goal is not to find and name all the weird things that happen in the human body but to improve people's lives. Many abnormalities cure themselves if left alone. Not all things people can name or study are real problems. As a principle, we should only be chasing things that make a difference in outcomes that matter.